The circular economy: a turning point for UK industry decarbonisation

In the face of intensifying regulatory pressure and volatile energy prices, UK industries are at a crossroads. The net-zero by 2050 commitment is no longer a distant ambition; it’s an operational mandate. And while cleaner energy and carbon capture remain vital, a compelling yet underexploited lever is emerging: the circular economy.

What if decarbonising industrial operations wasn’t just about cleaner inputs, but about using fewer inputs altogether—more intelligently and regeneratively? From British Steel in Teesside to craft breweries in Yorkshire, businesses across sectors are beginning to ask that exact question.

Understanding the circular economy beyond recycling

Let’s clear one thing up: the circular economy isn’t a fancy word for recycling bins in the break room. It’s a systemic shift in how goods are designed, produced, used, and recovered. At its core, it aims to eliminate waste, keep materials in use for longer, and regenerate natural systems. For industry, that means rethinking everything from procurement to end-of-life product strategies.

According to a 2023 report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and Material Economics, up to 45% of industrial emissions globally could be tackled through circular economy measures—without even considering clean energy switches. That’s huge. Especially in heavy sectors like construction materials, automotive, aerospace, chemicals and food processing.

UK sectors leading—or lagging—on circular practices

Certain UK industries are making notable strides. In construction, companies like BAM UK and Arup are pioneering reuse-oriented building designs, while the ‘Part Z’ initiative gains traction to embed embodied carbon limits into building regulations. The ReLondon initiative—backed by the Mayor of London—is pushing for circular construction sites, with pilot cases showing material savings of up to 25% per project.

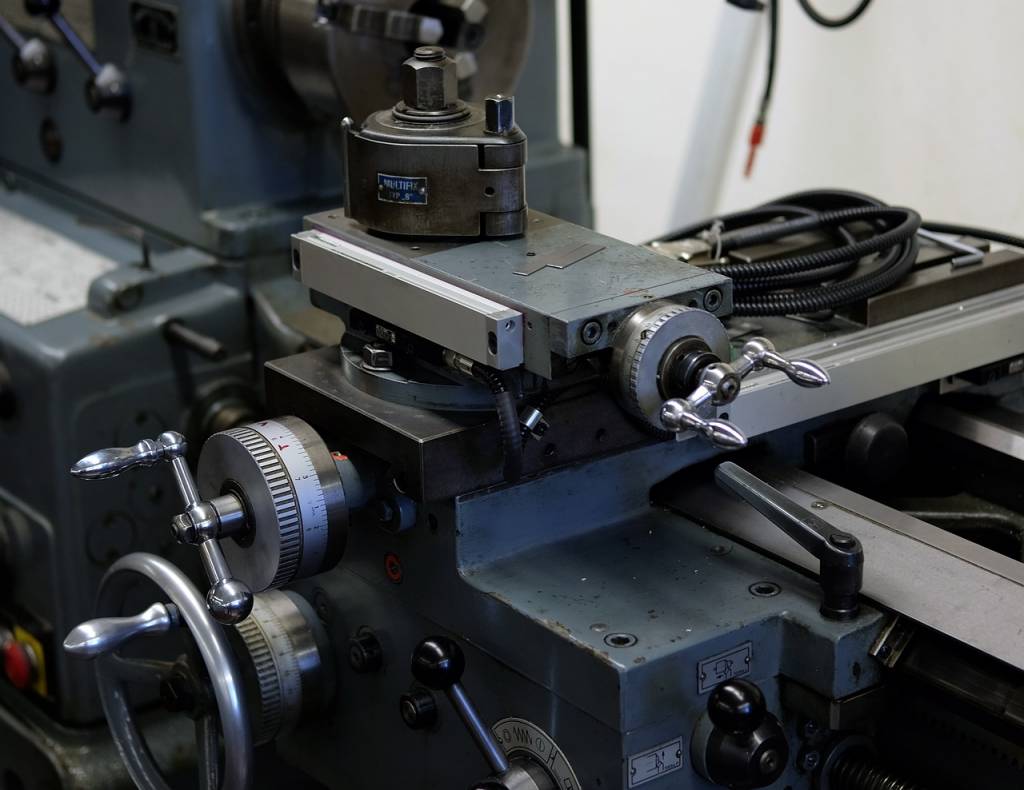

Meanwhile, in the steel sector, British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant has begun trials of electric arc furnace (EAF) technology that relies on scrap steel—potentially slashing emissions by 60–70% compared to traditional blast furnaces. But it’s not just about tech—it’s about securing reliable secondary input streams. A circular economy demands resilient reverse logistics and trust-based supplier ecosystems, which remain weak links across many UK value chains.

Why circularity equals carbon gains

Let’s take the aluminium industry. Producing primary aluminium is notoriously energy-intensive—up to 14 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of metal. But when reprocessed from scrap, emissions drop by over 90%. That’s the kind of delta that should have boardrooms listening hard.

Similarly, in the food processing sector, firms like Cranswick plc are embedding closed-loop strategies by converting food waste into renewable bio-gas across their facilities. According to WRAP UK, the food industry could reduce its emissions by 20% simply by implementing more circular sourcing and waste strategies—without major capex.

The message is clear: reducing material dependency often means reducing energy and emissions as a byproduct. Circular value chains aren’t just good environmental policy—they’re good carbon strategy.

Barriers: what’s holding back wider adoption?

If the potential is so obvious, why isn’t this happening faster? Field interviews with sustainability officers from mid-market manufacturing firms across the Midlands highlight three recurring frictions:

- Lack of infrastructure: Reverse logistics remains underdeveloped, especially for complex assemblies like electronics or automotive parts. Without easy take-back, reuse becomes a logistical fantasy.

- Policy gaps: Current UK regulatory frameworks still incentivise linear behaviours. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes are fragmented, and secondary material standards often lack industrial credibility.

- Upfront risk perception: Although many circular approaches lead to long-term savings, the transition entails short-term investments in redesign, training, and supplier alignment. In a tight-margin environment, that’s often a deal breaker.

Regulatory tailwinds offer a critical push

The good news: policy is starting to catch up. The UK Government’s Circular Economy Package, aligned with the EU’s directives, is redefining waste definitions and creating incentives for reuse. From 2025, tighter landfill bans and eco-modulated fees will pressure producers to embrace design-for-disassembly and material traceability.

Moreover, initiatives like the UKRI-funded Industrial Decarbonisation Research and Innovation Centre (IDRIC) are linking university research with industrial hubs to test and scale circularity innovations. Example: Tees Valley Net Zero cluster is prototyping closed-loop solutions in the process industries, including solvent recycling and CO₂ reuse in chemical production.

Still, regulatory alignment needs to accelerate. Industry is demanding clearer definitions, metrics and reporting norms. A 2023 survey by Make UK revealed that 68% of manufacturers see unclear guidance on circularity as a deterrent to action.

From linear supply chains to circular ecosystems

Embedding circularity requires moving beyond firm-level action. Industry-wide collaboration is vital. Consider the Catapult Network’s Smart Manufacturing programme: it brings together SMEs, multinationals and academia to share data on material flows, enabling component remanufacturing at scale.

Similarly, Jaguar Land Rover’s REALITY project demonstrates a closed-loop supply chain for aluminium, recycling end-of-life vehicles into new models with up to 75% recycled content—without compromising performance or safety. None of that happens in isolation. It’s coordinated ecosystem work, and logistics plays a crucial role.

Indeed, reverse logistics—once seen as a cost centre—is becoming a strategic asset. Companies like DHL Supply Chain are now offering turnkey circular logistics solutions for electronics and apparel sectors, including smart return systems, refurbishment, and re-commerce platforms. According to data from McKinsey, circular logistics could become a £4.3 billion market segment in the UK by 2030.

Digital tools enabling the shift

Digitalisation is the silent enabler of circular industry. Whether it’s digital twins to optimise process loops, blockchain for material traceability, or AI tools to predict part longevity, data is foundational.

One standout is Nottingham-based company Circulor, which offers blockchain-enabled supply chain tracking for raw materials. Initially aimed at ethical sourcing in mining, it’s now helping UK battery manufacturers trace cobalt and lithium, ensuring recycled content integrity and regulatory compliance.

Another is Stuffstr, a circular retail platform working with UK brands like John Lewis to incentivise customers to return used items via digital reward systems—changing user behaviour while feeding secondary material channels.

Steps for manufacturers to embed circular thinking

For industrial firms looking to operationalise circularity, here are key actionable steps:

- Map material flows: Understand where value leaks occur—waste streams, part degradation, process inefficiencies.

- Engage your supply chain: Co-develop reuse and recovery systems with suppliers and end-users.

- Pilot circular products or services: Start small—modular design, servitisation, spare part recovery—then scale from proof-of-concept.

- Embrace cross-sector collaboration: Waste for one sector is raw material for another. Share data and opportunities.

- Leverage existing platforms: Join initiatives like WRAP’s Circular Economy Hub or the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s CE100 to access tools, data and partners.

What’s next for UK industry?

Decarbonising through the circular economy isn’t a silver bullet—but it might just be the missing puzzle piece. While clean energy grabs headlines, using fewer materials, designing for longevity, and closing resource loops could slash industrial emissions faster and more cheaply than many realise.

The UK has the research firepower, the policy momentum, and enough cross-sector innovation to lead the way in circular industrial transition. The key question is: will manufacturers and policymakers move from pilot projects to systemic change?

For many UK businesses, the time has come to get serious about less. Less waste. Less carbon. And, ultimately, less risk in an increasingly resource-constrained world.